I’ve just stumbled upon this find on the blog of Daniel Gross about the art of convincing others.

Behind every idea is a fantasy, and that’s the real convincing part

The main premise of Daniel’s post is that behind every idea is a deeper, often hidden away fantasy that drives it. And focusing on that, rather than on the idea itself, makes for a much more convincing argument.

One doesn’t buy a car just to go from A to B. One buys this or that specific car, because they buy into the ethos of safety, or speed, or engineering that the maker imbues onto their models.

Arguably, most smokers don’t end up quitting because they’re afraid, or because they have calculated the risks for themselves, but rather because they truly want a freer way of life where they can have fun with their loved ones without being out of breath.

Equally, if you’d like to convince friends to go camping for the first time, talking up the sentiment of freedom is likely to be more effective than listing the features of the campsite itself.

How to best utilise this in practice

Daniel puts together a really interesting list of tools, which I have edited slightly below.

It can be used just as easily on yourself, to elicit a change of behaviours, as it can be on friends, family, or customers.

- Listen carefully – what’s the underlying fantasy that may be driving your friend, or your customer? What do they really want?

- Probe gently and don’t jump to conclusions – don’t put words in the mouth of your interlocutor; you’re trying to find out what they want, not what you would prefer that they want

- Counter-position, or play along – competing directly with a fantasy is one of the most common mistakes; it’s much more effective to draw up a different one that your interlocutor may like, unless of course you agree with the fantasy, in which case just play along

- Direct a movie – I really like this, and it’s about painting a vivid picture of the fantasy you’d like to convince your interlocutor of; it’s something you can do through any mediums (video, text, face-to-face conversation…)

- Be useful, be selfless – as with any interaction, it’s crucial to add value: make sure you have your interlocutor’s best interests at heart; it’s not as easy as it sounds, but it should be your leitmotiv, and it will always be remembered and recognised on the long run

Why does it even work

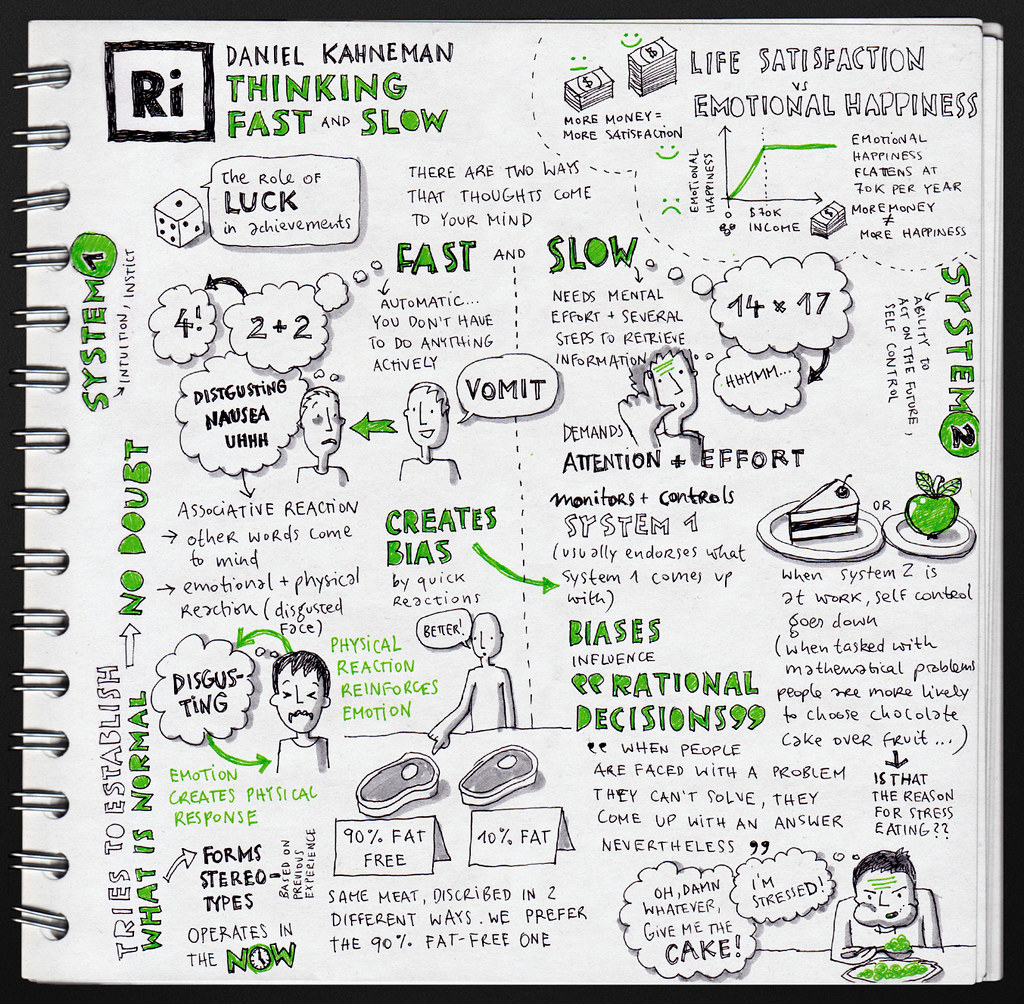

Well, as much as we’d like to think of ourselves as rationale decision makers, we aren’t.

From the seminal, fundamental thinking in Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking fast and slow to more contemporary examples of multivariant experiments, we’ve learned that we can be swayed by the smallest inputs, from the size of a button to how popular a product may be with complete strangers.

Conversely, this could be why the fantasy is more seducing than the idea, and ultimately more likely to induce a significant change. We want to picture ourselves in a different movie, and we do that at the back of our mind all the time.

Thus, describing the movie rather than the scene is more compelling.

And how it works for brands

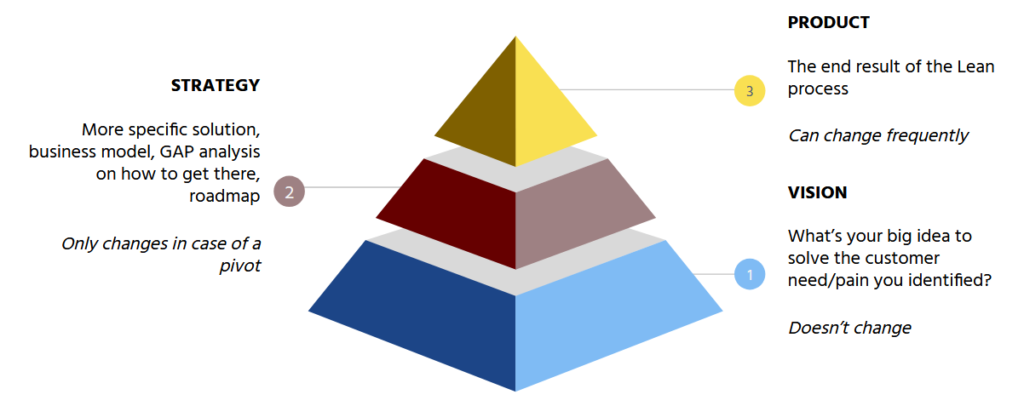

In brand speak, that’s why great brands have clear, strong, and aspirational visions/missions/statements. This then flows into the brand’s strategy, and its products, and how they will be introduced, explained, and sold.

Perhaps the best way to explain this is through the Lean Pyramid, in which:

- the base is the vision, which doesn’t change

- the middle part if the strategy, which rarely changes

- the top part is the product itself, which can/should change frequently